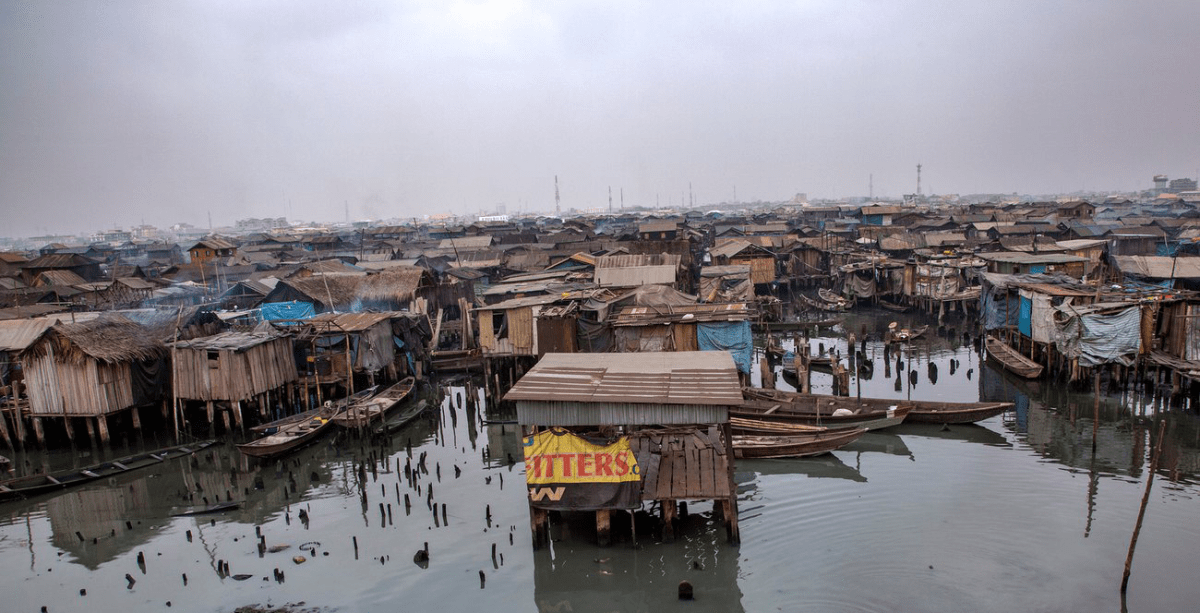

A community within a community as I would like to call it, flanked by water and land.

Waking up in Makoko is no different from waking up in any other part of Lagos, the hustle and bustle within the ‘Venice of Africa’ are reminiscent of the Megacity in which it is situated. The day starts out with men and women sailing to their different points of duty and half-naked children rowing their boats or playing on the wooden shacks. Life is just like anywhere else in the world; the sun sets and the stars come out to play; the only difference is Makoko is that slum in full view, spread out beneath the most travelled bridge in West Africa’s Megalopolis.

Slums evolve from the inability of migrants or low-income urban settlers to afford urban housing. Many are familiar with the idea of slums but not many know that there is a slum population of more than a billion people which is expected to double by 2030. The government is crazed with cooking up interventions for wiping slums when they ought to be finding ways for the inclusion of slums in city planning. Rather than excluding slums from the urban fabric of a city, just like Brazilian favelas, ‘they ought to be woven into the fabric of city living such that housing policies embrace and plan for the uniqueness of these settlements.

Makoko is one of such slums that has become a ‘nightmare’ to the government of Lagos and rather than find a way to embrace this slum, it has conveniently ignored her existence. Contrary to popular belief as an environmental eyesore, Makoko has succeeded as a form of a self-sustaining (sufficient) community despite lacking basic amenities/infrastructure.

It embodies the fundamentals that communities require to be self-sufficient such as the proximity of school and work to home, the reliance of individuals and the community on resources gotten within the same community. For example; fishing which is a trade common with the Makoko people and a huge generator of income serves the state as well as the people within the community, so also sand dredging and wood milling for the construction industry.

Makoko does not exist as a disease to be cured but rather should be given an opportunity to develop organically like other communities. Makoko has done well for itself as a community built and developed without government intervention. It is a true marvel that a site with such unsanitary condition battles not with communicable diseases but rather with non-communicable diseases. There is a lot to learn as designers and stakeholders in shaping the environment from a slum like this. And while we put our ears down to learn, we ought to begin to make plans for inclusion. Taking a cue from Alejandro Aravena; answers to these urban slum issues lie within the slums themselves.

The question then on our minds ought to be, ‘how do we create plans for embracing urban slums in our race for global urbanism and sustainable city planning?’.

The question then on our minds ought to be, ‘how do we create plans for embracing urban slums in our race for global urbanism and sustainable city planning?’.